Propulsion technology has steadily evolved over the past century, starting from piston engines all the way to the present era of turbofan jet engines. But innovation is always taking place behind the scenes, and the industry could be on the cusp of introducing a new form of propulsion that uses hydrogen as its primary fuel source. While hydrogen engines have already been in development for years, they are still a long way off from being ready for widespread commercial use.

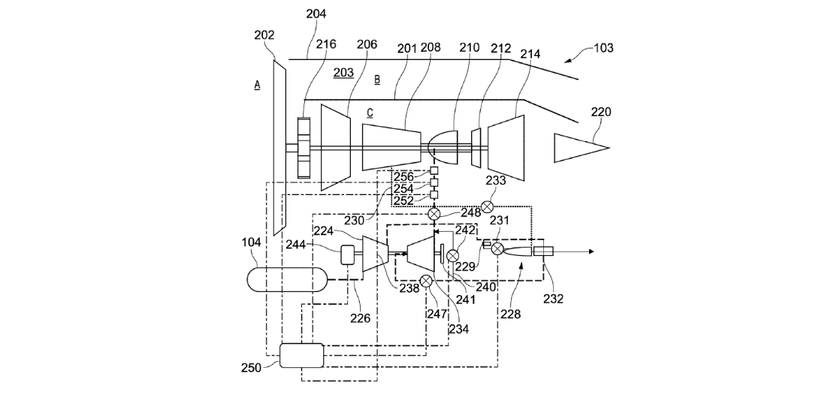

Leading enginemaker Rolls-Royce is pursuing its own hydrogen engine designs and recently patented a fuel system for a gas turbine engine configured to combust hydrogen fuel. This novel approach to hydrogen power could help solve one of the major problems of using liquid hydrogen as a fuel source, namely its extremely cold temperature. Rolls-Royce’s idea is to use a fuel turbine to heat the hydrogen fuel before it reaches the engine, creating a more stable combustion process.

Rolls-Royce Patents New Hydrogen Combustion System

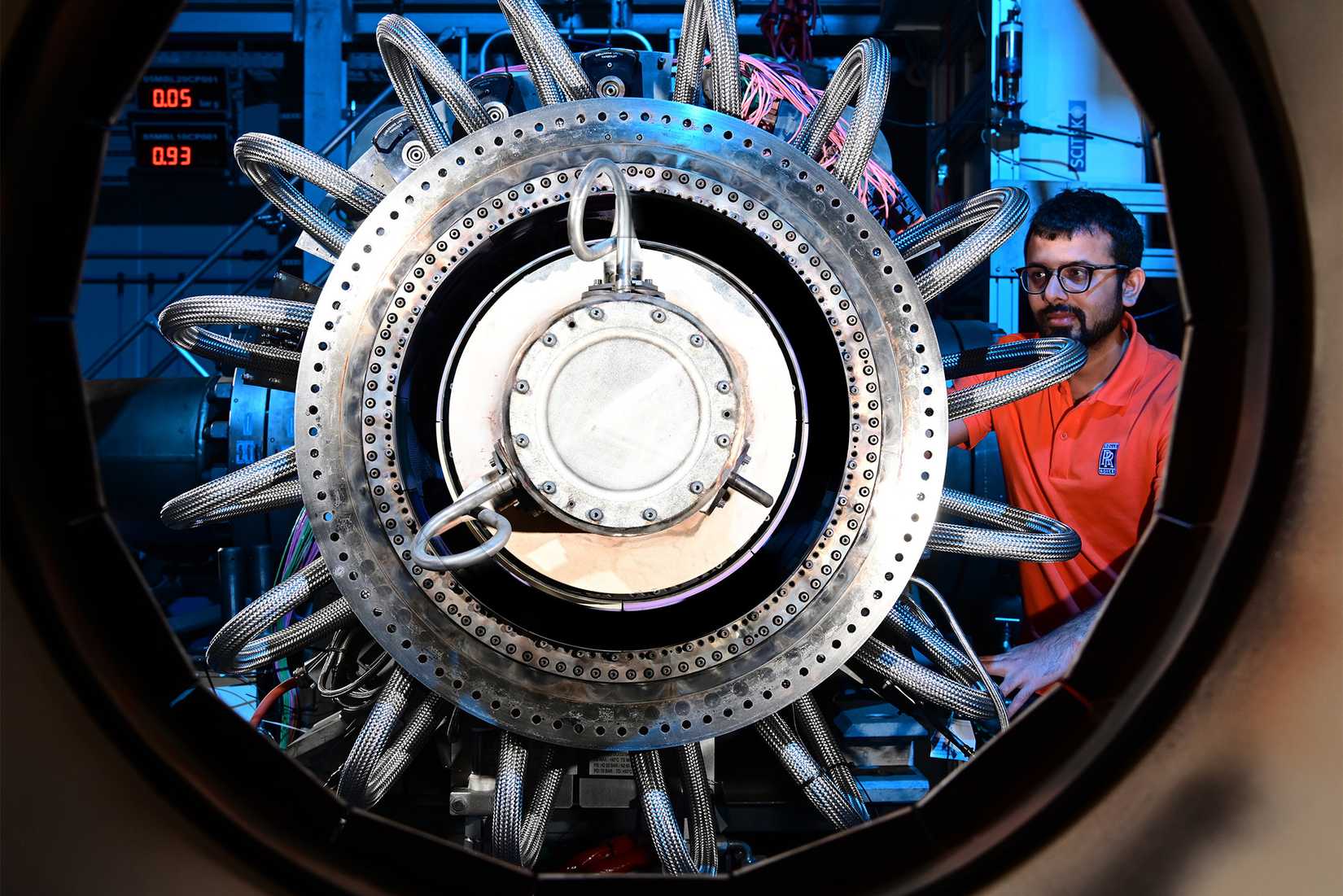

According to the patent filing, its new fuel system includes a main fuel conduit with a fuel pump “configured to operate on hydrogen within the fuel conduit to provide pressurized fuel to the core combustor of the gas turbine engine.” It will also feature an auxiliary combustor, which will burn a portion of the hydrogen fuel to heat the remainder of the fuel. In other words, it will be a self-sustaining system that diverts a small amount of hydrogen from the main fuel conduit to pre-heat the fuel.

While hydrogen is theoretically one of the cleanest fuel sources, in practice, it is one of the most difficult to implement on an aircraft. This is because hydrogen requires a larger volume of storage compared to traditional jet fuel, posing major problems for aircraft design and airport infrastructure. Liquid hydrogen also needs to be stored at ultra-low temperatures and has a more volatile combustion process.

Rolls-Royce’s proposed system would help solve both of these issues, providing a controlled and efficient fuel delivery architecture. While hydrogen fuel cells have shown much better practical feasibility, hydrogen combustion is a different story. Liquid hydrogen must be stored at -253°C, which means aircraft require insulated fuel tanks that can store it safely. But its lower density compared to jet fuel means these tanks will take up more space than conventional tanks, proving a headache for aircraft designers.

Small And Mid-Size Aircraft By Next Decade?

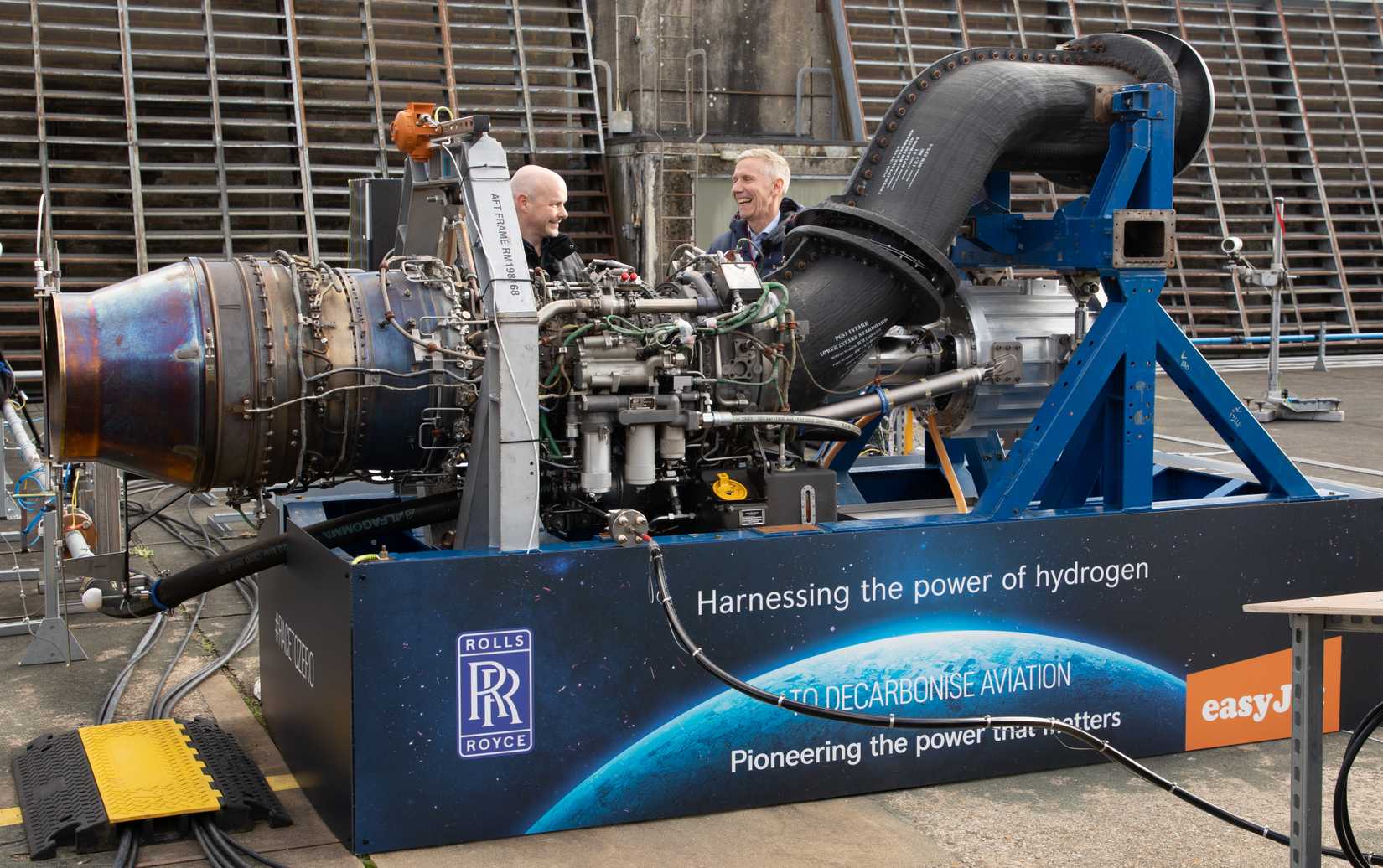

With years of rigorous development and testing still ahead, don’t expect to see hydrogen fuel-powered systems on a large commercial aircraft any time soon. The technology first needs to mature on smaller platforms before it can be scaled up to large passenger jets. Rolls-Royce is one of the pioneers in this field and is conducting comprehensive testing before progressing to flight testing.

The company aims to have a hydrogen-fueled engine ready to power small and mid-size aircraft from the mid-2030s onwards, although there is still a long way to go. It has already spent two decades exploring various hydrogen-powered concepts, including using hydrogen fuel cells as a substitute for electric battery power. Starting with light aircraft before the end of the decade, we can expect a global fleet of 30-40 seater planes introduced by the mid-2030s.

Rolls-Royce’s combination of hydrogen and gas turbine technology would be more revolutionary, although the enginemaker believes this would likely be viable for smaller aircraft only due to the complexities of hydrogen combustion. According to Rolls-Royce,

“While hydrogen can also be used directly as a fuel in a gas turbine, it is likely to start in the shorter-haul segments, where the aircraft range is shorter. Given volume limitations attached to the storage of hydrogen and the limited power density of fuel cells, for long range, SAF fuelling gas turbines will remain the most likely solution moving forward.”

Industry Looks To Hydrogen As Clean Fuel

When hydrogen is used in fuel cells, it emits zero carbon dioxide, which is why it is such an enviable possibility for the industry. Airlines and airports are under huge pressure to scale down their carbon emissions, while the potential lower costs down the line compared to jet fuel is a clear plus point. With the industry setting a 2050 target of achieving net-zero carbon emissions, hydrogen is one of the most promising technologies being looked at, although a pure hydrogen-fuelled aircraft is far more challenging to develop.

Instead, combining hydrogen with other fuel systems seems to be the most feasible option. Hydrogen-electric engines are already on the cusp of entering service, with some major stakeholders like ZeroAvia targeting entry dates for regional aircraft as early as 2028.

|

Program |

Size / Type |

Capacity |

Target Entry Date |

|---|---|---|---|

|

ZeroAvia (ZA600) |

Regional / Small Turboprop |

10–20 passengers |

Mid-2026 |

|

ZeroAvia (ZA2000) |

Regional / Turboprop |

40–90 passengers |

2027 |

|

Airbus ZEROe |

Commercial Airliner |

Up to 200 passengers |

Recently Delayed |

|

Universal Hydrogen |

Regional Turboprop |

40 passengers |

2026–2027 |

|

H2FLY |

Regional Aircraft |

30–40 passengers |

Mid-2025 |

The EU’s Horizon Europe project is providing investment for Rolls-Royce’s hydrogen research, covering engineers, scientists, and specialist test equipment needed to advance hydrogen combustion testing. The initiative has already made great progress, with Rolls-Royce on the cusp of starting full-scale ground testing of a hydrogen gas turbine. Rolls-Royce is also a part of the EU’s Clean Aviation initiative, which is exploring various technologies to develop more efficient, carbon-friendly propulsion. Specifically, the CAVENDISH project — which stands for ‘Consortium for the AdVent of aero-Engine Demonstration and aircraft Integration Strategy with Hydrogen’ — is looking at hydrogen as an aviation fuel.

Hydrogen’s Aviation Future Unclear

While hydrogen has great promise as a zero-emission fuel, industry stakeholders hold mixed positions on its potential for scale-up global use. Besides the aircraft design challenges of using and storing hydrogen, another key obstacle is the lack of global infrastructure to support it. Current production levels of usable hydrogen are very low, and the cost of scaling up infrastructure is considerable. Ultimately, airports and energy companies are uncertain about investing billions into infrastructure if the demand doesn’t materialize.

Airbus recently announced it was delaying its ZEROe program, suggesting it could push back its targeted 2035 entry date by five or ten years. The planemaker was due to use an Airbus A380 as a testbed for hydrogen engines, but has now scrapped these tests. Airbus launched its ZEROe project in 2020 and explored several different possibilities before settling on a fuel cell design. Airbus said,

“Hydrogen has the potential to be a transformative energy source for aviation. However, we recognise that developing a hydrogen ecosystem – including infrastructure, production, distribution and regulatory frameworks – is a huge challenge requiring global collaboration and investment.”

The UK’s Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) has revealed it will expand its Hydrogen Challenge, an initiative that provides funding for decarbonization solutions in aviation. The consensus among most developers is that hydrogen will remain a smaller-scale complement to traditional fuels, rather than being an immediate replacement fuel. This will make hydrogen useful within hybrid systems, pairing it with electric or sustainable aviation fuels to reduce global fleet emissions.

Could Larger Airliners Run On Hydrogen?

We will likely see a rapid rise in the popularity of hydrogen-electric regional aircraft in the coming years, but the question remains whether the technology can ever be put on a large airliner. Skeptics of hydrogen’s future in aviation believe it is too impractical for long-haul flying, taking up more space than conventional jet fuel. This means operators would have to sacrifice either range or capacity in order to accommodate larger fuel tanks.

Rolls-Royce has admitted that the feasibility of fueling large commercial aircraft, particularly a widebody, is questionable due to the technical complexities of storing hydrogen. This would require fundamentally different aircraft designs to accommodate the extra fuel needed to fly the same distance as a kerosene-powered jet.

Whether manufacturers can figure this problem out remains to be seen. Such an aircraft may be possible to build safely, but it would likely come at the expense of passenger capacity and/or range.

Green Hydrogen Production Concerns Remain

Although hydrogen releases only water vapor when used as a fuel, this does not mean its usage was entirely carbon neutral. This is because hydrogen can be produced through polluting methods, such as by coal and gas, which does not contribute towards the industry’s decarbonization efforts.

Green hydrogen is the cleanest form of hydrogen production, achieved using electricity from renewable sources such as wind, solar, or hydro power. As Rolls-Royce puts it, “only hydrogen produced using renewable energy sources is truly carbon neutral,” but most of it in use today was produced using coal and gas.

The current costs of green hydrogen are also significantly higher than fossil-fuel production, so it remains unclear if the infrastructure could be built to support enough production. The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that green hydrogen could reach $1.50–2 per kg by 2035, making it more competitive with jet fuel prices, but this would require a significant ramp-up of current production capabilities.